Included in the packaging for the physical LP of Father John Misty’s sophomore follow up, I Love You, Honeybear, is a thin pamphlet titled, “Exercises for Listening.” It’s an extensive instruction manual for the album, consisting of humorous lists for each song printed in an anachronistic aesthetic reminiscent of a sliver of paper you would find in a vintage novelty hypnotism record. This is the second time Father John Misty or Josh Tillman, the author of the text and music, has supplied a supplemental reading to the lyrics with his records. His first album, Fear Fun, included his surrealist, hyper-satirical novel, Mostly Hypothetical Mountains, printed in minuscule font on both sides of multiple, giant fold-out posters. Tillman is a frustrated literary writer, with an obsessively verbose and hyper-analytical philosophical style, but like his obvious influence, David Foster Wallace, he’s able to pull it off. He’s a gifted singer-songwriter and preternatural entertainer, using his albums as a Trojan horse for his writing—probably because it’s easier to him than undertaking the demoralizing process of publishing a book in the 21st century. Tillman’s supplemental texts are an integral part of the greater experience of his albums—although, I don’t remember how far I got in Mostly Hypothetical Mountains.

Included in the packaging for the physical LP of Father John Misty’s sophomore follow up, I Love You, Honeybear, is a thin pamphlet titled, “Exercises for Listening.” It’s an extensive instruction manual for the album, consisting of humorous lists for each song printed in an anachronistic aesthetic reminiscent of a sliver of paper you would find in a vintage novelty hypnotism record. This is the second time Father John Misty or Josh Tillman, the author of the text and music, has supplied a supplemental reading to the lyrics with his records. His first album, Fear Fun, included his surrealist, hyper-satirical novel, Mostly Hypothetical Mountains, printed in minuscule font on both sides of multiple, giant fold-out posters. Tillman is a frustrated literary writer, with an obsessively verbose and hyper-analytical philosophical style, but like his obvious influence, David Foster Wallace, he’s able to pull it off. He’s a gifted singer-songwriter and preternatural entertainer, using his albums as a Trojan horse for his writing—probably because it’s easier to him than undertaking the demoralizing process of publishing a book in the 21st century. Tillman’s supplemental texts are an integral part of the greater experience of his albums—although, I don’t remember how far I got in Mostly Hypothetical Mountains.

In anticipation of the new record, manifestos on his grand concept were disseminated in various iterations on his corresponding social network accounts and multiple self-penned press releases. A brief summary of all this text: he attempted to write about falling in love with his wife, Emma, and the resulting profound self-transformation enabled by that event, without the use of sentimentality or other artificial conventions. I Love You, Honeybear is also a comedic deconstruction and examination of loving and living in a mediated capitalistic world.

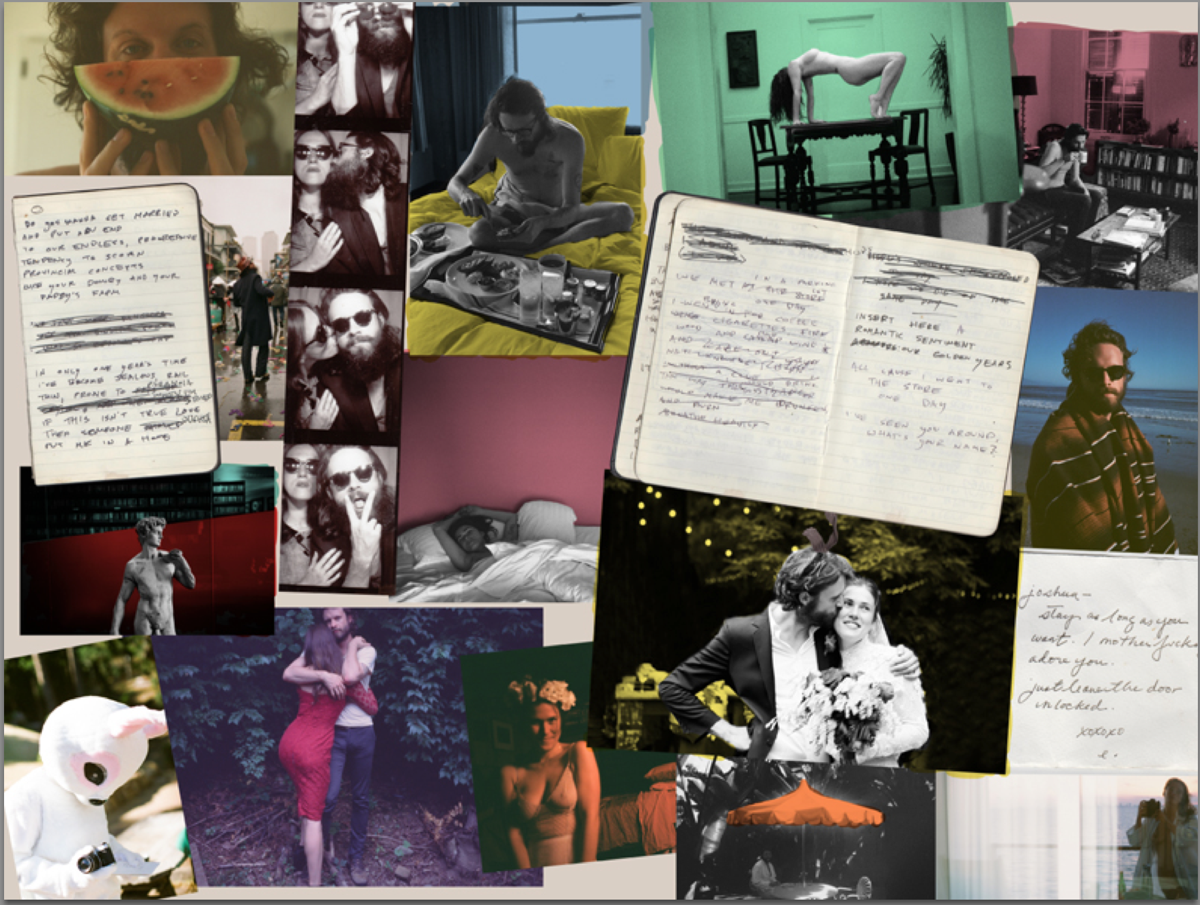

Josh and Emma Elizabeth Tillman. Photo from Emma Elizabeth Tillman’s Tumblr / Instagram user: @tennesseebunny

Or as Josh put it in his press release, “My ambition, aside from making an indulgent, soulful, and epic sound worthy of the subject matter, was to address the sensuality of fear, the terrifying force of love, the unutterable pleasures of true intimacy, and the destruction of emotional and intellectual prisons in my own voice. Blammo.”

Not only has he achieved this ambition, but he transcended it.

In the same way women listen to Beyoncé, Fear Fun became my swagger record, especially in the wake of difficult breakup. Although, I would never consider myself a ladies man as accomplished as Tillman, Father John Misty indirectly helped me learn to better interact and really love women. Women wanted Josh Tillman—even though he was perceived as a little bit of a jerk—and men wanted to be him. As a frustrated neurotic artist/slacker/philosopher, I aspired to that. And maybe, my realized self that emerged from my own searching could be a little more earnest than Father John Misty.

Like the synchronicity I felt with Fear Fun, I Love You, Honeybear found me at just the right time and space, subjectively paralleling my own little romantic narrative, like a humorous, verging on profound, letter received from a friend. I don’t know how much this uncanny phenomenon has to do with metaphysics—or if it’s just my own construct—but the rare and exceptional book, film, or album can create an altered consciousness.

Now, after false starts, fun misadventures, and ayahuasca ceremonies, like Josh, I by chance met a woman, who is Something Else. I wasn’t looking to be in a relationship, and, after years of feeling self-conscious about women, was just getting into the zone of living without attachment and enjoying the life of a space-age bachelor. Over idealizing and being dependent on a woman scared me, and was the downfall to more than one of my past relationships. Good women are rare, but we also have to be in the right place in our own life to appreciate them.

Here’s my blurb: This album facilitated in the awareness of the deeper love I have for my girlfriend!

I Love You, Honeybear is described as a concept album about a guy named Josh Tillman. Miraculously, unlike most marketed “concept” albums, it has a definitive narrative structure and theme. The critical attention toward track order is highly evident and seems to be a blatant response to the culture of streaming and downloading. It implements the classic album’s dramatic arc that’s as old as Aristotle’s Poetics, Joseph Campbell, and/or OK Computer: Opening establishing song, slight counterpoint second song—usually the hit single—then a few songs playing with tension and release, climaxing to a violent orgasmic, cathartic intermediary song, next, two progressively unwinding tempo songs to take it on home to the last song. Fin. These are also usually ideal make-out/sex albums.

On the day of the release, I decided this would be a good romantic record to put my girlfriend and I in the mood, and it had the potential to be yet another album I associate with a relationship. Yep. There’s that word. I’ve been with this woman every night for the last two months, and strangely, this isn’t exhausting or annoying. Kaley is this calm, but by no means passive, companion that will engage in endless conversation about everything, and when we’re not in deep discussion, it feels completely natural to sit in silence together and/or spend hours immersed in our own work. When dating an artist, it’s important to have mutual tolerance for each other’s temporary madness. There’s never a struggle for attention between us. We balance each other out. A romantic simpatico on this level is special, and, even though she is physically gorgeous, her mind and soul are what really attract me. This kind of love is what this record is about.

After a domestic cooking exercise in my cluttered apartment with Kaley, I put I Love You, Honeybear on my turntable for the first time, while we ate on the couch among the stacks of books, empty bottles, and dirty dishes. We listened to the album about four times in a row, drinking and eating, discussing the record at length, interspersed with sex, and because of the weed we smoked, the precise timeline of the events and observations that follow get a bit hazy.

Track 1: The title track, “I Love You, Honey Bear,” acts as the overture to the record. It presents the themes and their dualities: Josh and Emma’s love, their psyches, and the absurdity of the outside world that they sometimes want to tell to fuck off. Father John Misty and producer Jonathan Wilson comfortably twists the music tropes and lineage of the Hollywood Vampires of the 70s. Josh doesn’t hide his influences. We have Nilsson, Lennon, and Newman—but also Scott Walker, Dory Previn, and Neil Young, plus a multitude of literary and philosophical heroes such as Žižek, Sartre, Vonnegut, Allen, and Jodorowsky.

The slightly deranged strings and ache of the steel guitar are instrumental signifiers that can’t be resisted. The girlfriend is really digging it. She’s familiar with Misty and the YouTube video of his mocking post-post-modern performance at the Spotify offices, with a mobile karaoke and light machine playing a cheesy MIDI version of the track from SAP, Tillman’s satirical response to the culture of music streaming services.

The first audible chuckle from Kaley is to the lyric, “You’re bent over the altar and the neighbors are complaining. That the misanthropes next door are probably conceiving a Damien.” Although my favorite lyric in the song is: “I’ve brought my mother’s depression. You’ve got your father’s scorn and a wayward aunt’s schizophrenia.”

It seems like an off-putting revelation to hear humor used in such a serious production—even though, a smattering of artists have done this effectively throughout the history of popular music. Kaley explains Tillman’s comedic timing with a brilliant observation: He creates a sarcastic tone by creating an illusion of improvisation—that is, the musical emphases (higher pitches, downbeats) often do not align with the lyrical emphases (emphasized syllables or important words within a sentence). It’s like my slightly, stuttered phrasing when I’m making up funny lyrics on the spot along to the melody of her ring tone. She just blew my mind again. I love this woman.

Unlike many rock and roll lyrics, which are easily ignored, Father John Misty’s are integral to the transmission of the song. Like Dylan’s, they demand a close reading. Josh’s lyrics are raw and conversational, or as he put it to the Irish Times, “I think that my loftiest ideal for my music is that by writing so intimately about myself that in some kind of counter-intuitive way, it kind of becomes universal.” He doesn’t shed the indirect, sardonic style of the last record, but hones it to use that same mode in a direct way. Like the raw sincerity of solo John Lennon, he is singing exactly what he is thinking.

Track 2: We come to “Chateau Lobby #4 (In C for two Virgins).” The Spotify single. It’s the track that Emma and Josh defiantly made an abstract official video for on their iPad for their wedding anniversary. This is the first explicit indication that Emma is something Josh can’t explain because everyone else is boring, and, by the repetition of the phrase, “first time,” apparently, it’s the first time he has felt this quality of love. But like all good drama, Tillman’s conditioned cynicism and doubt provide the thematic tension of the record. Josh’s id and neurosis play the foil.

As she unfolds the large poster of a photo collage that Emma Elizabeth Tillman designed for the lyric sheet, Kaley says,“They look beautiful,” in that uniquely feminine tone, which is uttered when a women is projecting her relationship on someone else’s romantic scenario.

The dim light, provided by the few dead light bulbs I’ve been meaning to fix, set the unintentional romantic ambiance, and somehow let me better see the cosmic swirl of the sunflowers in Kaley’s irises: a shade of blue green that plays in a beautiful color palette with her dirty blond hair. It could be my contacts and crappy vision, but it’s difficult to directly stare in someone’s eyes without your focus blurring.

Track 3: The synthetic “True Affection,” is Father John Misty’s biggest stylistic departure to date. It follows the organic Mariachi horns of the previous track. Tillman utilizes the laptop Moog sonics of trap beat-Postal Service/Bjorkish-electronic music, and is probably the closest thing FJM will ever come to EDM. Everything artificial is an intentional decision to convey the disconnect, and the human things lost in translation during an unavoidable, substitute digital courtship on the road with Emma using “strange Apple devices.” It’s not Aphex Twin, although listening to the weird soundtrack Tillman wrote for his wife’s intriguing film, The History of Caves, I eagerly look forward to his innovative future experiments. They might be like Scott Walker’s later albums that scare the shit out of me, but for now Josh is not radically re-inventing his own musical language. With his mastery of the King’s English, he seems to enjoy experimenting with established signifiers of the genres he inhabits.

Around this point in the album my girlfriend and I put our forks down, and heavy petting commenced on the couch. I think she really likes this song. That sexy beat probably reminds her of Bjork. She notices while kissing me that she is laying on her iPhone, checks to see that it didn’t sex butt dial anyone and that it’s set on “do not disturb,” and throws it onto the ground. The “strange devices” have been banished.

End of Side A. Just when we’re getting started. I get up bare-chested to flip the record. More wine, honey? Since I Love You, Honeybear is a double LP, there’ll be a lot of getting up to switch them. You couldn’t have made this a little easier for us vinyl fetishists, Josh?

Track 4: “The Night Josh Tillman Came To Our Apartment” implements manic pixie dream girl glockenspiel and a sitar. It’s an ode to the archetypical hipster ditz that desperately hangs out after the show to try to bang the lead singer of Foxygen or the drummer of the Fleet Foxes. Tillman sings, “She says, ‘like literally, music is the air [she] breathe[s]’ And the malapropos make me wanna fucking scream. I wonder if she even knows what that word means. Well, it’s ‘literally’ not that.” This song also begins the Felliniesque masculine thought experiment that becomes a psychological thread of the record. The ladies man uses the girl in the song to analyze all “other women” or past “other women” and comparing them to Emma, not superficially or aesthetically, realizes the rarity of his intimacy with Emma.

Things are getting pretty hot and heavy on the couch now. We should probably move it to the bedroom, or we can stay on the couch. Novelty is good. Don’t worry, Mom. I’ll spare you the details—even though you had me edit the sex scenes in your romance novel.

Track 5: The baby-makin’, slow soul song, “When You’re Smiling And Astride Me.” It comes at just the right time. Being a soul boy, I was overcome by the muffled ‘70s snare sound. The slinky Harrison guitar. The dusty electric piano. After hearing the lyrics, “There’s no need to fear me. Darling, I love you as you are when you’re alone. I’d never try to change you. As if I could, and if I were to, what’s the part that I’d miss most? When you’re smiling and astride me I can hardly believe that I’ve found you. And I’m terrified by that…You see me as I am, it’s true. The aimless, fake drifter, and the horny man-child Momma’s boy to boot.”

I looked to my naked girlfriend, bathed in lamplight, and said, “Oh shit, this is our song.”

This is the sea change of the album and the self-described redemptive, transformation of Tillman in the story. Josh sings, “That’s how you live free. To truly see and be seen.” Josh and Emma accept and see each other for who they are, collectively trying to dismantle the bullshit. Their mutual connection allows them a safe place to be vulnerable and brutally honest with each other to do so.

Like Josh, when it comes to romance, over analysis and skepticism can plague me. I read Sex at Dawn. Monogamy is just an enculturation. Blah Blah Blah. I’ve spent an exhaustive amount of time second-guessing my emotions. People say that when you’re with the right person there’s no doubt. You just know and everything is perfect. No. I don’t think it works this way, but I am aware that most of the doubt I experience is usually a distorted reflection of my uncertainty towards myself. Thinking to myself, this doesn’t look exactly like what I imagined in my head. I thought you would be French or at least have some kind of accent. What’s with this sick fascination Americans have with the foreign and the exotic? I know you ladies do, too. I’ve observed you ogle Gael García Bernal. All of Kaley’s ex-boyfriends are foreign.

Prolonged intimacy breaks down all the facades that are used to woo each other. When you first start dating, you’re on your best behavior, desperately trying to hide anxiety and flaws because of this irrational belief that maybe one of those flaws is a deal breaker.

Track 6: “Nothing Good Ever Happens At The Goddamn Thirsty Crow,” is a country song with avant-garde flourishes. It’s content is self-explanatory: a relatively unheard depiction of a ladies man’s blue balls on the road amongst a sea of groupies. Then he reverses the scenario, grappling with his own jealousy when Emma is hit on at a bar. Josh exercises his god given right to brag about what he loves about his wife, referring to her as his genius. In Emma, Josh has found his intellectual and artistic equal.

He sings, “But my baby, she does something way more impressive than the Georgia crawl / She blackens pages like a Russian romantic. And gets down more often than a blow-up doll.” Libido compatibility in a committed relationship isn’t everything, and subject to impermanence, but when I experience it, it’s awesome that it’s one less thing I have to worry about in this particular moment.

Track 7: “Strange Encounter” is the precursor to the climax of the album. The background vocals vaguely echo the motif in Fear Fun’s “Misty’s Nightmares 1&2,” which was a haunting rumination on the ghosts of girlfriends past. In “Strange Encounter” one of Josh’s conquests overdoses in his house. He’s freaked out by the emptiness of his debauchery, and begins to long for something real, singing, “Don’t be my last strange encounter.” The phrase takes on dual meanings. He refers to a girl in the song, and as self-destructive as his empty dalliances were, fidelity means that he will never have another “strange encounter.” Emma is also his last “strange encounter,” collapsing all other possibilities, as Josh gains something real. True love scares the shit out of him, when he realizes the danger of being vulnerable with another person.

Kaley glances down at the gatefold record jacket. Stacey Rozich’s artwork for the album features beautifully painted children’s book illustrations of anthropomorphic animals and creatures, acting as surreal symbols, archetypes of the characters and themes of the songs. Josh is depicted as a naked baby suckling at the breast of a Madonna figure on the cover. The Oedipal image was the only specific instruction he had for the art, and he feels it’s a summarizing articulation of the record. I didn’t buy the $40 deluxe Dioramic, Meta-Musical Funtime pop up edition, with colored vinyl, because I’m a starving artist. I’m not falling for your gimmicks this time Father John Misty.

Track 8: “Ideal Husband,” enters with pummeling drums and bass, and a lyrical allusion to Julian Assange taking Tillman’s files. We can’t hide our dirty secrets anymore. Josh lays it all out for Emma with no filter. Every shred of guilt, insecurity, doubt, and loathing is exorcised and confessed, before taking the last dive into the unconscious oblivion of the male psyche. The song is a primal scream, a sonic equivalent to the aftermath of a reckless bachelor party. He shows up at Emma’s at seven in the morning singing, “Said something dumb like, ‘I’m tired of running / Tired of running / tired of running!’” It’s cliché, and maybe stolen from the monologue of High Fidelity or some other romcom. Then, the last lines, “Let’s put a baby in the oven!” which in the phrasing sounds macabrely funny, and, “Wouldn’t I make the ideal husband?”

Track 9: The couple then resurfaces, naked and free, to comment on the world around them in the last two wind-down tracks of the album. I heard “Bored in the USA” in the Apple Store over the in-store speakers. I was waiting in an unnecessary Kafkaesque situation for a Genius to replace my MacBook’s frayed charger, which essentially failed as a product of planned inherent vice. As I looked around at the others with Apple products in their laps like sick pets, our collective dependence on these strange devices (marked with a half bitten apple: the sign of the fall of man) became increasingly apparent. The song provided ridiculous synchronicity to this moment. It’s not only a satirical cultural critique, but also a disclosure of Josh’s fear of commitment and the potential boredom of marriage. The utilization of a laugh track in the middle third of this song is a brilliant gesture.

Our clothes and underwear are in a scattershot pattern throughout my small one bedroom. We are both completely naked. We need our lovers to escape the mundane and the tyranny of our thoughts, and through the acceptance we experience with intimacy, see reality for the way it really is. Josh and Emma’s mattress, and this unintentional, distressed leather couch, are sensual refuge from the insanity described above.

Track 10: The second to last song, “Holy Shit,” is a unification of the two interdependent types of songs on the record. It’s a long list of contemporary hash tags for the human condition. Like Allan Watts says, it’s impossible to differentiate the individual from its surroundings. As much as Josh and Emma want to ignore the stupidity of the outside world, maybe their compassion won’t let them be so selfish.

In an interview with Pitchfork Josh called intimacy an “antibody to narcissism.” I would add: Love is a selfless act. It’s not all about YOU and what you want or think you need. The practice of love generates the fierce will necessary to transcend our selfish nature and care for another, and like daily meditation, this process can be liberating.

To quote Slavoj Žižek from a video for the Guardian, “For me the highest form of freedom is love. Love means that you totally dedicate yourself to one other person. You renounce one of the key freedoms of choice: to exchange sexual partners and so on. This freedom is now gradually taken away from us…by online dating sites… I think our idea today is love without the fall…No! Free love is the fall! You are walking along the street, you slip on a banana peel, a lady helps you, and maybe it will be the love of your life, you cannot predict it. Without this fall love is not love. True freedom means looking into and questioning the predispositions of everything that is given to us by our hegemonic ideology. To question everything including the notion of freedom itself.”—Coincidentally, Josh now wears a banana pin on his black velvet blazer.

I met Kaley in Real Life. My friend Brittney was bringing a “female” friend out with her to Soul Night. Although memory is creative in hindsight, I distinctly remember the exact moment I saw and checked Kaley out through the noise of the hipster crowd. It was significant. She believes it was a perceived blip of precognition. Later we bonded over our fascination with Ram Dass among other things, and it was apparent she was on my wavelength.

Track 11: The last song is inevitably an eternal panty dropper. Much to Josh’s chagrin, it is destined to become the Cadillac of hipster wedding songs. The composite of track 4 might request it from her wedding DJ because she’s oblivious to the fact that there’s another song on the album that is about her. Although I call dibs on “When You’re Smiling And Astride Me” for my contingent, and, for the context of this review, potential wedding. (Sorry Ma, at least I’m deeply contemplating this monogamy stuff now, and that should make you happy.) It’s similar to that saccharine song Adam Sandler sings to Drew Barrymore on the airplane in The Wedding Singer, Ben Fold’s “The Luckiest,” or that Ben Gibbard song that was presumably written about Zoey Deschanel—except “I Went To The Store One Day,” is so real and devoid of affectation there is a good chance that it will induce existential shivers, while you sit in the afterglow, listening to the sound of the record when it runs out of groove. It could have been a case of set and setting, but Kaley and I were both a little teary eyed.

Josh arranges the song as a post-coital serenade with a single acoustic guitar, Italian tremolo mandolins, and a string section. The third verse features a humorous, futuristic, hypothetical tangent on married life, growing old, and his inevitable death, fully self-aware of his cynicism towards sentimentality: “Don’t let me die in a hospital. I’ll save the big one for the last time we make love,” he says in diminished croon, probably half-wincing, but satisfied in finding something genuine out of all things in those last words.

Just like Slavoj’s banana peel, Josh by chance met Emma in the parking lot of the Laurel Canyon Country Store.

As Lennon observed before him, only through love, do you see beyond the egotistical projections of a neurotic, and to the flickery dimension that’s much deeper, primordial, and ineffable.

Writing about love without it sounding like a Hallmark greeting card is a slippery process. The challenge of writing this review must be just an approximation of the struggle Josh went through making this record. I lived with this album for a weekend, and like Kaley, am not sick of it one bit. I Love You, Honeybear deserves multiple listens over a lifetime. I close read the culmination of the text provided like a scholar, intimidated by the process of trying to say something about love that wasn’t already articulated more effectively by Tillman. I felt engaged in an intense one-sided Socratic dialogue with Josh about love and its ontological implications. In a meta-twist that might pleasure Charlie Kaufman, I became so enmeshed with Father John Misty’s simulacrum, I needed my identity back. My girlfriend observed the beginning signs of my anxiety, and provided the encouragement to build the confidence to finish this piece. Only you can save yourself from yourself, but a good woman can help.